January 11, 1880. Friday.

11 o’clock in the evening

In the morning, I wrote a letter to Iordan in response to his gracious note from yesterday.

I set out to collect donations for the church.

Shtankovsky, despite all the recommendations from Novodevichy and all attempts to move him by letter, did not contribute.

"Is he at home?" — "No, he has gone to the office."

I went to Ivan Petrovich Lesnikov, to whom I had written a letter.

"Is he at home?" — "Busy, come back in an hour."

I waited at Fedor Nikolaevich’s. When I presented myself again—"Not at home," came the curt and stern reply.

I called on Vasily Nikolaevich Khitrovo regarding Jerusalem. The Greeks in Jerusalem: "Will the Arabs leave? Well then, the revenues will not diminish, and there will be fewer concerns..."

I dined at Fedor Nikolaevich’s.

At the Putyatins’, I drank Japanese tea; Madame Posiét also arrived there. She sat for a long time but spoke little—mentioning, among other things, the arrangement of the Empress’s rooms in the Winter Palace, where even at the windows, the temperature remains perfectly equal to that of the rest of the room, as pipes have been installed around the windows. She also mentioned that Konstantin Nikolaevich is soon departing to accompany the Empress on her return from Cannes to St. Petersburg.

At six, as promised, I was at the home of Protopriest Nikanor Ivanovich Bryantsev. He, too, recounted numerous captivating stories about the Jews (how they once attempted to abduct a baptized Jew abroad, how later his father requested baptism himself, and much more), as well as about the persecutions and denunciations against him (St. Tikhon). He inquired about the Mission.

Present at his home was a Jewish doctor—a colonel, chief physician at a military hospital—who had acquired all that he needed before his baptism and had converted entirely out of conviction, such that he required no cross from his sponsor (Archimandrite Vitaly). While I was there, he even gave five rubles to a poor man who had been brought in by the police.

At eight o’clock, Nikolai Ivanovich left for some committee, while I hurried to the Lavra bathhouse and bathed among the workers—cramped quarters, good steam, free conversation, and the excessive zeal of the Balkan man, Ivan.

January 12, 1880. Saturday.

At the third hour of the night.

A dull and burdensome day, as dull and burdensome as my entire sojourn in Russia. I was often bored in Japan, but in Russia, I am almost always so. Where, then, is it better? Wherever and whenever there is a true calling. Let this be remembered and felt when I am in Japan.

In the morning, Father Isaiya came. He visits frequently. Were I not in the Bishop’s favor, he would not come. He brought the sacred vessels from Zheverdeev—he had not purchased them but had promised to do so. We agreed to go together next Sunday to the Marble Palace—he to serve, I to see the Palace and to visit Il[ya] Alexandrovich Zelenoy, who had invited me for this Sunday.

Avdotya Dmitrievna Kovanko came—to offer upon the altar of the Mission only her burning and weeping heart. Thanks even for this. She invited me on Thursday to her friend Maderach (almost like Sedrach...), who has gathered thirty rubles for the Mission. I gave my word.

And all of this is good, all of this is virtuous! But it would still be more virtuous if those in dire need were not reduced to the state of beggars.

This collecting of alms enrages me—the necessity of knocking on doors and receiving rude rejections like those of yesterday, in the most literal sense of the word. For the sake of acquiring humility—perhaps; but what if such things, as happened to me yesterday, provoke instead bitter laughter? I laughed in several places, yet at the bottom of my soul lay anger, a foul aftertaste. There is something unnatural, something forced in these collections for those who must solicit them. Nowhere in the Holy Scriptures is this to be found. David merely proposed. Paul merely advised and set forth a rule.

Let this matter of collecting be left to God! I do not know what will come of it; I only know that there will be a church in Japan, but how it will be established—I do not know.

I expect much moral torment in this endeavor. But what of it? Let me be torn to pieces, so long as there is Christianity in Japan!

I went to the Akathist in the Krestovaya. It was slightly artificial, with half-tones and interruptions. The reading was done by His Grace Hermogenes—I was not pleased. The singing was superb, but the absence of Sakharov among the basses was keenly felt. What a melodious and powerful bass he had! One would cling to it with one’s ear. And this did not diminish the effect of prayerfulness. Today’s singing, however, was somewhat lacking; only occasionally did it stir the soul to tears.

I was bored and melancholy. At the fourth hour, I went to Father Nikolai Kovrigin; found him beneath the heavens—seven children, an old man bedridden. I promised to plead on his behalf before I. P. [Ivan Petrovich] Kornilov.

At Fedor Nikolaevich’s, I took several copies of the report. At the same time, the old Count Orlov-Davydov was ascending to him. On the steps: "Be off!" —to a servant assisting him. He had come, it seems, to ask Fedor Nikolaevich to become the spiritual father of his family in place of the late Protopriest Shishov. Fedor Nikolaevich received him most simply, altering neither his attire nor his demeanor, though he had known in advance of his arrival.

I left five copies of the report with "Japan and Russia" for Konstantin Petrovich Pobedonostsev, in accordance with his earlier discourse on the matter.

I attended the Vigil at Krestovaya. Among the choir was an aged soprano, whose voice, it seemed, did not make a particularly pleasant impression.

With Father Joseph, the censor, we agreed to visit Admiral’s widow Rikord on Tuesday.

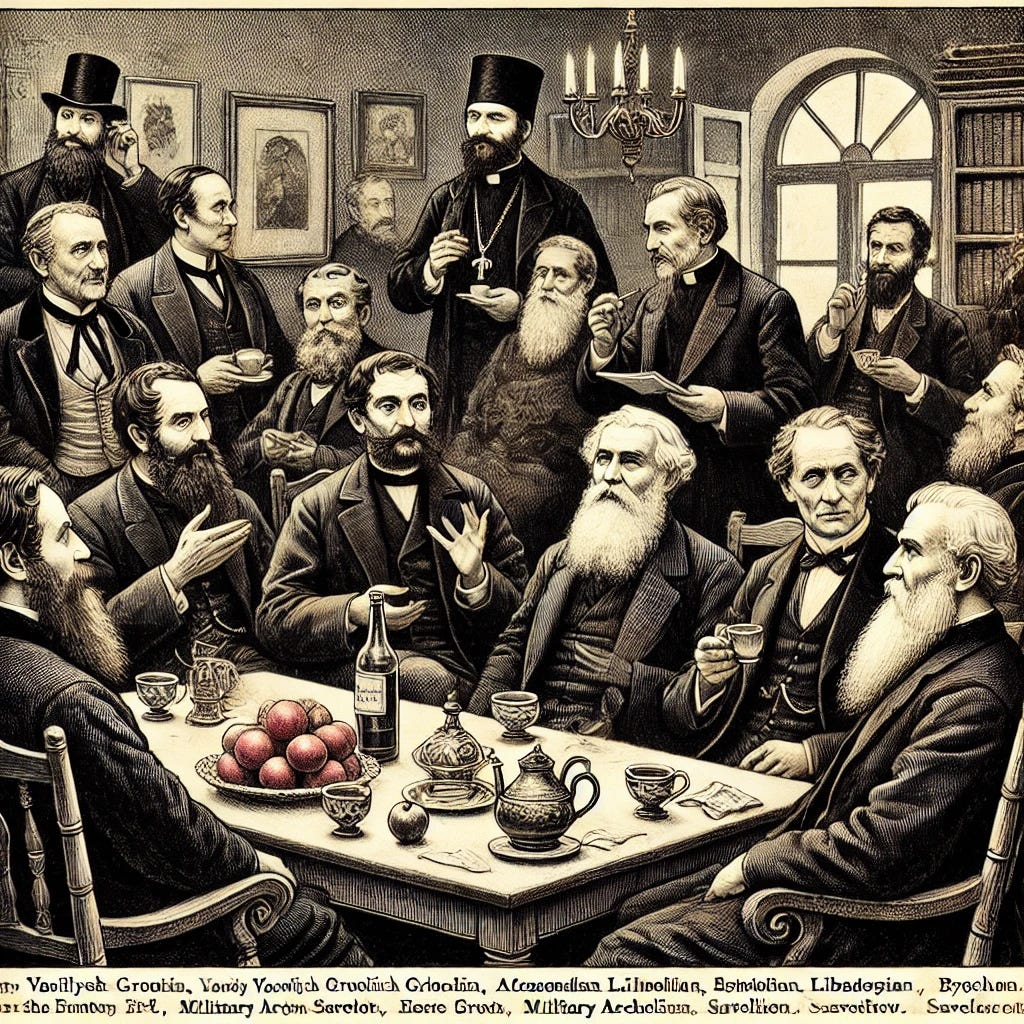

At the ninth hour, I was at I. P. Kornilov’s. On Saturdays, gatherings are held at his house. I arrived first, followed by V. V. [Vasily Vasilyevich] Grigoriev—the most intelligent and interesting among those present. Then came Alexander Lvovich Opukhtin, the curator of the Warsaw Educational District; Bychkov, the librarian; Grot, the academician; Saveliev, the military archaeologist; P. A. [Petr Andreevich] Giltebrandt, editor of "Old and New Russia"; Zolotarev, Kossovich, Savvaitov, P. A. [Petr Alexandrovich] Vasilchikov, and others.

All murmured, all were dissatisfied. Alexander Lvovich spoke of Kotzebue, the governor-general of Warsaw—how he flatters the Poles, how the Poles are again raising their heads and taking the upper hand. Everything was about something ill in Russia today.

And I wished to ask these elderly, mostly bald or graying gentlemen—why, then, do you not unite, why do you not found, for instance, an honest journal, or something of the sort? A void, a lack of substance in such a serious, learned society. Imagine such a gathering of men in any Western country—how much more substance there would be!

Tea at the beginning, apples and grapes in the middle, supper of two courses and pastry at the end.

I spoke with Grigoriev about the feudal system in Japan.

Much tobacco smoke.

What engaged me most were Grigoriev and Opukhtin—on Poland (he was presented to the Sovereign today, who kissed him on the head and said, "Endure" [in Poland])—and also the absentmindedness of our most amiable and kind-hearted host.

Notes on Translation:

The phrase "как хотели похитить заграницу одного крещёного" was somewhat ambiguous; it likely refers to an attempt to smuggle a baptized Jew abroad, rather than kidnapping him within a foreign country.

"пр. Тихон" likely refers to St. Tikhon, but the abbreviation might indicate an honorific or specific reference.

"забалканец" (translated as "Balkan man") could indicate a person of Balkan origin or simply someone overly zealous in behavior.

"Нашел под небесами" (translated as "found him beneath the heavens") is an idiomatic phrase that suggests extreme poverty or destitution.

"чуть не Седрах" ("almost like Sedrach...")—the reference is uncertain but might allude to the biblical figure Shadrach (Sedrach in Russian), possibly implying religious devotion or endurance.

"Я хохотал в нескольких местах, а на дне души — злость, дурной осадок." (translated as "I laughed in several places, yet at the bottom of my soul lay anger, a foul aftertaste.")—the contrast between laughter and bitterness is notable, emphasizing frustration rather than amusement.

"С дискантом старым, по-видимому, производит не особенно приятное впечатление." (translated as "Among the choir was an aged soprano, whose voice, it seemed, did not make a particularly pleasant impression.")—"дискант" refers to a high-pitched voice, likely a male soprano (boy treble) rather than an adult soprano.

"куда больше бы содержания!" (translated as "how much more substance there would be!")—captures the lament over the lack of meaningful discourse compared to Western intellectual circles.

Housekeeping:

I decided to keep the translation notes from ChatGPT, as they interested me.

It seems to me a strange thing to rely on computers to translate these Diaries, but our volunteers don’t have time to work on this project, and there is no budget yet to hire translators, so here we are in this peculiarly 21st-century situation, enlisting computers to do God’s work, because the humans are too busy. What a strange time we live in!

Reflections:

This passage particularly struck me:

This collecting of alms enrages me—the necessity of knocking on doors and receiving rude rejections like those of yesterday, in the most literal sense of the word. For the sake of acquiring humility—perhaps; but what if such things, as happened to me yesterday, provoke instead bitter laughter? I laughed in several places, yet at the bottom of my soul lay anger, a foul aftertaste. There is something unnatural, something forced in these collections for those who must solicit them. Nowhere in the Holy Scriptures is this to be found. David merely proposed. Paul merely advised and set forth a rule.

Let this matter of collecting be left to God! I do not know what will come of it; I only know that there will be a church in Japan, but how it will be established—I do not know. I expect much moral torment in this endeavor. But what of it? Let me be torn to pieces, so long as there is Christianity in Japan!

I’ve run into the same problem, except in asking for donations; we are trying to get out of the orbit of an Orthodox country, Russia, so that we can visit the Orthodox mission in Japan, but nothing I seem to say or do will elicit more donations.

Indeed, in trying to stir up my American compatriots to love and zeal, the backlash on Twitter was intense, so I closed that account so as to cut down on the noise.

I titled our fundraiser ‘The Love of the Great Body Has Not Grown Cold’, so as to challenge Scripture-minded donors, but the challenge has not worked, and only $350 has been raised.

So I am working my butt off, trying to pull in income any way I can, and looking at switching careers to more profitable ones.

It seems that expecting American and European Christians to care about Christians in Russia and Japan is a futile effort.

Well, so be it; if you don’t care, I do, and I will work my fingers to the bone so that Elena and I can accomplish our mission.

If you don’t care, it doesn’t matter. I care.

St. Nicholas and I are in different situations: He is a priest with an already established mission, longing to return to Japan. We are stuck in Russia's orbit, longing to get to Japan for the first time.

But we are both dealing with indifferent, cold-hearted Christians who cannot think of helping others abroad.

Every time I read more of these diaries, I feel closer to my patron saint, a true friend who understands.

And every day, I love my wife more, my only helper in a world that does not understand what is important.