January 8, 1880. Tuesday. 7 o’clock in the evening

In the morning, I wrote a letter of gratitude to Father Kosma and took it to Father Isaiah, along with some brochures to be sent to him. At ten o’clock, I set out to see Nikanor Ivanovich Bryantsev to remind him about the promised donation concerning the Tsarevna. I found him engaged in conversation with the most wretched-looking Persian Mohammedan, who wished to join the Orthodox Church. The Persian understands Russian very poorly and, it seems, seeks baptism mainly in hopes of obtaining some material assistance. I suppose that here, one must act as one sees fit!

Father Nikanor is primarily a missionary to the Jews; he has already baptized about six hundred of them. However, people of all nationalities desiring baptism are sent to him.

He recounted a very touching story of the baptism and wedding of a Jewish woman, whose father had remarked to Father Nikanor: “I do not merely wish to kill her—that I could do at any moment—but I would like to cut her into tiny pieces.”

He spoke at length about the obstacles in his path; fortunately, he is a man of great strength, deeply experienced, and extremely courageous—he is not intimidated by anyone (as seen in his disputes with S. Bor. Potemkina, where he simply commanded her: ‘Be silent!’).

On the spot, he donated fifty rubles from a sum sent to him by Stakheev from Yelabuga for charitable deeds and advised me to write to him.

Regarding items from the Palace, he said there were many icons that could be given away and promised to speak with the Palace steward.

As for my presentation to the Tsarevna, he remarked that it was an extraordinary event: “Until now, only two individuals had been presented and had spoken with the Tsarevna—Metropolitan Makary and you.”

From there, I visited the Vladimirsky Archpriest, Dean Sokolov, to inquire about donations from the Church—he was not at home.

I stopped by the Putyatins’. Olga Yefimievna was pale and weak, having caught a cold, but she perseveres; she asked me to verify a transcription of ‘Praise’ that had been written in Russian letters from Japanese musical notation—she knows the Japanese alphabet correctly.

January 9, 1880. Wednesday.

In the morning, Father Nikolai Kovrigin arrived from San Francisco. He recounted many of the quarrels there and defended himself. The poor man—one cannot help but pity him—he has seven children; the ecclesiastical authorities granted him a pension of half his salary—1,500 rubles per year—but he has no position and no reputation. I promised to speak on his behalf to the Metropolitan and Ivan Petrovich Kornilov, in hopes of securing a place for him in Switzerland.

While he was present, a member of the Archaeological Society, Alexander Nikolaevich Vinogradov, arrived, recommending himself as a painter for the Japanese Mission. He speaks eloquently and eruditely, is well-versed in the East, but seems more of a theoretician than a practical, skilled painter. I promised to visit him this evening to view his iconographic collections.

Leaving with Kovrigin at twelve o’clock, I went to visit Pyotr Andreyevich Giltibrandt. His wife, Maria Maksimovna, received me very warmly, treating me to salmon, which she had fetched herself, and liqueur.

Pyotr Andreyevich, as always, spoke charmingly, mentioning, among other things, how ‘Novoye Vremya’ is corrupting morality—a sentiment with which I agree, having occasionally read ‘Novoye Vremya’ and encountered vulgar stories such as ‘Nana.’

At the Novodevichy Monastery, they showed me the torn vestments and other liturgical garments I had collected so far—it seems that nearly all of them are fit only for burning. I requested to be informed when Mother Juvenalia would conduct the burning so that I might learn from it.

From there, I went to Konstantin Vasilyevich Belevsky, the chaplain of the Naval Corps—he was not home.

At Jordan’s—they were dining, and I did not wish to intrude.

At Vinogradov’s—he was not in, as I had arrived slightly earlier than promised.

Back to Belevsky’s—he was resting, and I did not wish to disturb him.

At Fyodor Nikolaevich Bystrov’s—I found letters from Japan, written shortly after the receipt of my letter, and the second issue of ‘Shōgakuzasshi.’

After reading them, I visited the Putyatins. I found Olga Yefimievna ill in bed; I shared some excerpts from the letters, but not everything, as her sisters were present.

January 10, 1880. Thursday.

In the morning, the Metropolitan summoned me and informed me that the Ober-Procurator had declared that funds for the Mission had been included in the State budget.

‘Then, I suppose, congratulations are in order,’ he concluded.

He then spoke about the fundraising for the church. I admitted candidly that my efforts were not going well. His, however, fared better. Bazilevskaya had brought him ten thousand rubles, requesting only that her donation remain confidential. Lesnikova, a widow, contributed one thousand; someone else, I believe, gave another thousand.

Then, the Metropolitan declared that he was pledging to the church the nineteen thousand rubles that had long been entrusted to him by a donor for discretionary use.

With accrued interest, the sum had now grown to approximately twenty-two thousand.

He recounted the history of this donation, which in part concerned Father Alexei Kolokolov, about whom the Metropolitan spoke with great sympathy. The gist of it was that the donor had wished to be buried near Father Alexei and to have a church built over his grave. However, Father Alexei was transferred to the Georgievskaya community, the donor was buried elsewhere, and the money, according to a notarized will, was entrusted to the Metropolitan’s discretion.

I spoke about San Francisco and the documents I had brought to Beletsky and which he had left in my care.

The Metropolitan took the petition from the Slavs to the Synod regarding the construction of a church (I kept a copy as a mere formality) and said, ‘Please reply that I have passed it on.’

Regarding the church, he remarked that he already knew everything in advance.

‘Allow me to say a word on behalf of Nikolai Kovrigin,’ I said.

‘What of him? Everything that could be done has been done—his case was dismissed, and he was granted a pension,’ he replied and proceeded to recount the matter… He knows all the details of the disputes and scandals there and remembers everything.

‘Let him petition for any diocese he wishes, but I will not take him into mine’—which, in his view, included even the foreign territories under his jurisdiction.

In the evening, I visited Shchurupov. The church plan both pleases and displeases him; we shall see what the Metropolitan says—it will be built as he blesses.

At eight o’clock, I visited Konstantin Petrovich Pobedonostsev; he inquired in detail about my audience with the Tsarevna and remarked, ‘The Tsarevich deeply regretted not being present; he will notify you when you may have an audience with him.’ I requested an opportunity to be presented to the Tsarevich.

Madame Abaza was also present—she speaks Russian poorly, but nearly everything was conducted in Russian—such courtesy!

When Katerina Alexandrovna receives guests, she is incomparably gracious; one must admire this quality, so highly developed and extraordinarily charming among our high society.

Baron Osten-Sacken was also there.

Konstantin Petrovich confirmed that the Mission’s funding had indeed been included in the budget, but conditionally—a further inquiry had been sent to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Sacken remarked that this must be a misunderstanding, as the Holy Synod had already consulted the Foreign Ministry and received confirmation that there were no objections.

Among other things, Sacken mentioned the arrival of Baron Rosen—making it quite awkward to discuss Pelican and his wife; I hastened to change the subject. From Konstantin Petrovich, I learned that the marriage between Sophia Gavrilovna Pelican and Adam Petrovich Chebotaryov had already taken place.

Housekeeping:

What did you think about the newspaper-style illustrations I added to this one? Many of these situations are hard to find pictures of, because none exist, so I thought additional illustrations might be tasteful here and there.

I would much prefer to do them without AI, if an artist could be located who could do illustrations in the style of an 1800s newspaper.

Reflections:

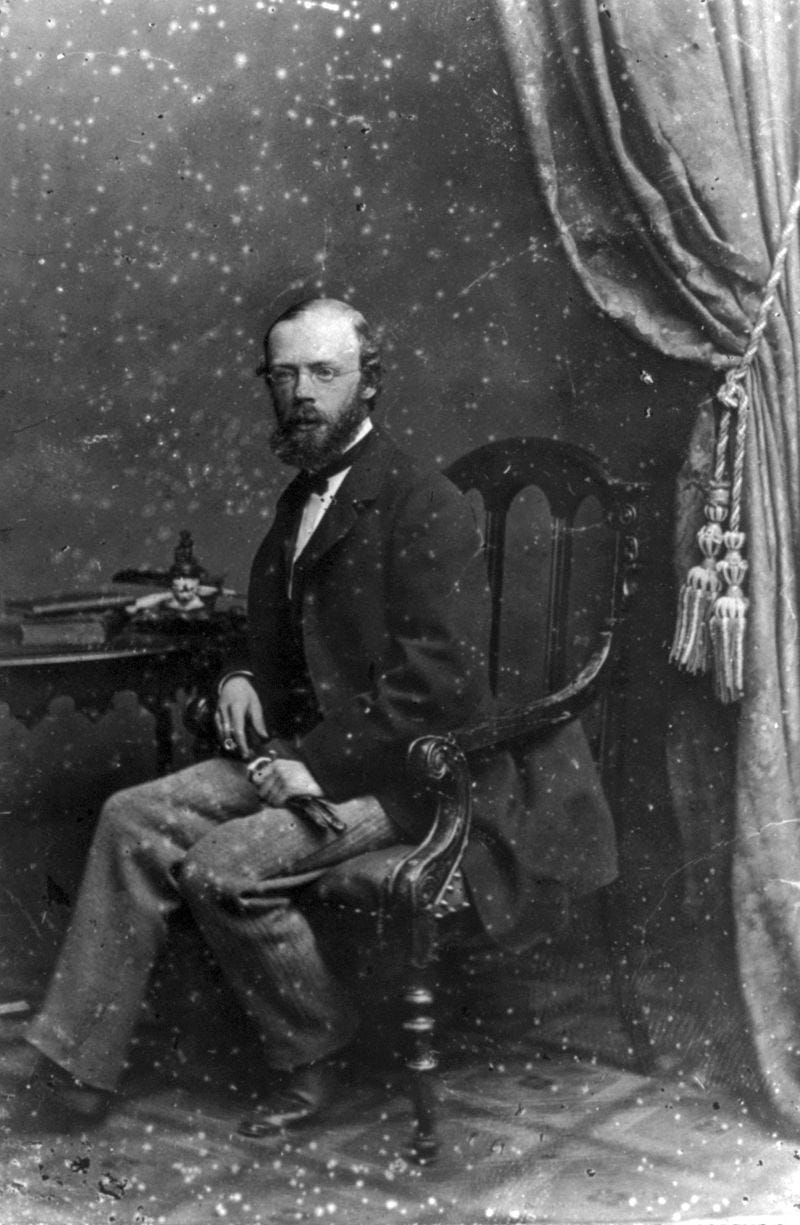

I’m even more impressed by this Fr. Nikanor. I wish I could find a photo of him, but none exist online; apparently there is a collection in the Library of Congress and one in Alaska.

Given the era in which Father Kovrigin lived, photographs might be scarce or nonexistent. However, historical archives or collections related to the Russian Orthodox Church in Alaska and San Francisco during the late 19th century might contain relevant materials. For instance, the Alaska State Library houses the Michael Z. Vinokouroff Collection, which includes photographs and documents pertaining to the Russian Orthodox Church in Alaska and Russian America.

Additionally, the Library of Congress holds archives of the Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church of America, Diocese of Alaska, which feature photographs from the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Regardless, this excerpt moved me:

Father Nikanor is primarily a missionary to the Jews; he has already baptized about six hundred of them. However, people of all nationalities desiring baptism are sent to him. He recounted a very touching story of the baptism and wedding of a Jewish woman, whose father had remarked to Father Nikanor: “I do not merely wish to kill her—that I could do at any moment—but I would like to cut her into tiny pieces.” He spoke at length about the obstacles in his path; fortunately, he is a man of great strength, deeply experienced, and extremely courageous—he is not intimidated by anyone (as seen in his disputes with S. Bor. Potemkina, where he simply commanded her: ‘Be silent!’). On the spot, he donated fifty rubles from a sum sent to him by Stakheev from Yelabuga for charitable deeds and advised me to write to him.

What a man.

As for my presentation to the Tsarevna, he remarked that it was an extraordinary event: “Until now, only two individuals had been presented and had spoken with the Tsarevna—Metropolitan Makary and you.”

I noticed in one entry that St. Nicholas was complaining about the longing and boredom being unbearable, and that while he was rubbing shoulders with the elite in Imperial St. Petersburg at the time! Imagine being around Hollywood stars or Elon Musk or Donald Trump and then claiming you were bored out of your mind! You’d have to be heavenly minded! (Or have a lot more common sense than we moderns often have!

And look at this…the power and money and prestige of the elites had no hold on the heart of St. Nicholas, they were as ordinary men to him, and he was one of only two men (the other a Metropolitan, higher-ranked than him) to see the Tsarevna!

Orthodoxy allows you to hold your peace when things are going badly around you, and to not get big-headed when things are going well.